“The name of Bow Street became revered by honest citizens and feared by the dishonest.”

Alan Cook and Peter Kennison

The origins of Bow Street

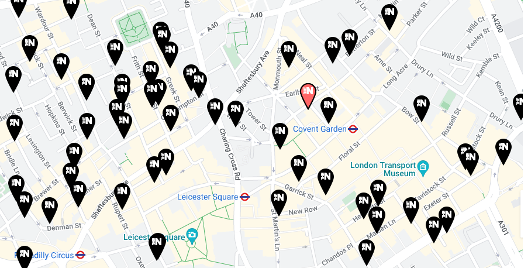

I recently took part in a guided tour of Bow Street and the various cultural emblems it hosts – including The Royal Opera House and The Police Museum. Bow Street is a thoroughfare in Covent Garden, named after its characteristic bowed shape, visible in this map. Although the area is now synonymous with glitzy pre-show glamour, and the tourist thrum emanating from Covent Garden – present even at 10 am, when the tour was taking place – Bow Street has had a tumultuous and gritty history, none of which would have been possible had it not been composed of such contrasting elements.

A map of Bow Street

“It was built to be residential,” our guide tells us, watching our eyes widen. To imagine this perpetually stimulated area as residential is no easy feat. Once the theatres were built, however, the area rapidly saw an influx of theatregoers of course, and, with the larger crowds, an influx of organised and petty crime, as well as prostitution. During this period, police forces did not exist! The building opposite the Royal Opera House, No.28 Bow Street, was established as the first Metropolitan Police Service for the Bow Street Runners by Henry Fielding, a playwright primarily known for his restorative comedy, in 1750. The building was constructed to match, if not attempt to exceed the Baroquian beauty of the Royal Opera House, our guide tells us. Fielding’s crossover from theatre to crime control is physically symbolised in the way these two buildings stand opposite one another, mirroring each other in more ways than their architecture and design.

Concentration of nightlife

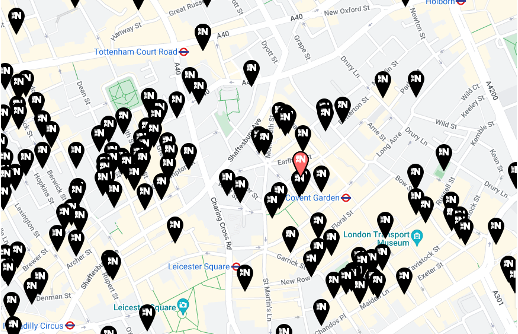

Statistics report the West End to be the most criminally active area in London till date. The maps indicate an extremely high frequency of bars and restaurants in the Covent Garden area, and in the vicinity – Tottenham Court Road, Leicester Square (Soho). Thus, this increases the likelihood of drunken crime and violence. The crime rate of the WC2E9DD postcode currently stands at 1294.4, classified as high (10/10). Nonetheless, this area also serves as the home of the West End theatres. The overlap of these locational purposes creates a unique, semi-glamorous, semi-gritty atmosphere that is specific to the Covent Garden area.

Bars in Covent Garden, Leicester Square, and Tottenham Court Road

Restaurants in Covent Garden, Leicester Square, and Tottenham Court Road

The duality of royalty and criminality

It is interesting to note the dual presence of institutions assigned royal patronage such as the Royal Opera House and the Royal Ballet School, and the rate of crime in Covent Garden. Locationally, it contributes to these two environments equally. On the one hand, it is situated centrally and is highly connected by two tube stations (Covent Garden, Holborn). Additionally, the map below highlights Covent Garden’s proximity to the higher-earning areas of London: Oxford Circus, Regent’s Park, Blackfriars, and Saint Paul’s – indicating a demographic that can access leisure services like the theatre. On the other hand, the nightlife fosters a criminal medium in the area.

The juxtaposition of utopian and dystopian elements

From ‘Spaces of Utopia and Dystopia: Landscaping the Contemporary City’

The investigation in this paper provides an interesting lens of analysis on the co-existence of utopian and dystopian pockets in contemporary cities. The writers theorise that utopian moments are sometimes ‘created’ in cities, in juxtaposition to surrounding ‘dystopian’ areas. The high density of consumption spaces, such as theatres in this instance, create a utopian fantasy that distracts from the dystopian atmosphere present in sections of the city. Films such as Last Night in Soho by director Edgar Wright solidifies the image of the neighbouring area of Soho as heavily dystopian through its horror/thriller genre and its visual presentation of Soho in fluorescent, inorganic colour palettes.

Last Night in Soho, Edgar Wright

Thus, the insistent utopia of theatre culture and the West End in Covent Garden coexists with the inevitable air of dystopia created by the crime and sometimes eerie nightlife of Soho.

One traces this coexistence in the history of Bow Street and its role in the cracking down of crime in London, that thus acknowledges the inevitable dystopia of London as a contemporary city. And, across the street, the growth of utopia through the flourishing of the Royal Opera House.

Chinatown, Soho

References

Crime rates by postcode (no date) Crystal Roof. Available at: https://crystalroof.co.uk/report/country/uk/crime (Accessed: February 1, 2023).

History (no date) Bow Street Police Museum. Available at: https://bowstreetpolicemuseum.org.uk/about-us/history/ (Accessed: February 1, 2023).

Lloyd, A. (no date) Theatre Land from 1800 to 1870.

MacLeod, G. and Ward, K. (2002) “Spaces of Utopia and dystopia: Landscaping the contemporary city,” Geografiska Annaler, Series B: Human Geography, 84(3&4), pp. 153–170. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0467.00121.

McLeod, L.-A. (no date) The Covent Garden Journal–then and now and in-between, The Covent Garden Journal–Then and Now and In-Between. Available at: http://lesleyannemcleod.blogspot.com/2012/08/the-covent-garden-journal-then-and-now.html (Accessed: February 1, 2023).

Stages and Cells of Covent Garden (no date) Royal Opera House. Available at: https://www.roh.org.uk/tickets-and-events/stages-and-cells-of-covent-garden-details (Accessed: February 1, 2023).

Theatre, +E. (2014) London’s west end: Vibrant or violent?, Everything Theatre. Available at: https://everything-theatre.co.uk/2014/01/londons-west-end-vibrant-or-violent/ (Accessed: February 1, 2023).